Early Palestine

Earliest Records

Section titled “Earliest Records”The term Palestine can find its the root of the word “Peleset”, referring to the Philistines the population inhabited the area between the Mediterranean Sea and Jordan River. It became more commonly used in the late Bronze Age, with archaeological evidence from Egyptian and later Assyrian sources confirming the term to describe the native inhabitants of that region.

Evidence of the the term Palestine can be found multiple in Egyptian hieroglyphs even today, here is an example from 1150 BCE:

Wall relief of philistines captives, mortuary temple of Ramses III Medinet Habu, Theban Necropolis, Egypt (I, Rémih)

Wall relief of philistines captives, mortuary temple of Ramses III Medinet Habu, Theban Necropolis, Egypt (I, Rémih)

Greek Period

Section titled “Greek Period”One of the most well known examples of the term Palestine to describe the central geographic area in the Middle East can be found in the famous Histories of Herodotus,430-424 BCE. The Greek word Παλαιστῑ́νη or Palaistī́nē was mentioned in multiple places e.g. Book 1:105. In this context, he refers to Palestine being part of wider geographic region that encompassed both modern day Syria and Palestine.

Roman Period

Section titled “Roman Period”The Romans also referred to the area as Palestine in a conscious effort to demarcate the administrative region. During the Roman and subsequent Byzantine sovereignty, Palestine was governed as a distinct imperial province. The Roman and Byzantine rule, whilst imposing their own administrative and cultural structures, did not erase the local identity of Palestine but rather amalgamated with it.

Early Muslim Rule

Section titled “Early Muslim Rule”From the mid-7th century onwards, Palestine became woven into the fabric of the Arab and Muslim worlds. The Islamic influence permeated every aspect of life in Palestine, the land was held high esteem in the Muslim world, second only in holiness to the sacred cities of Mecca and Medina.

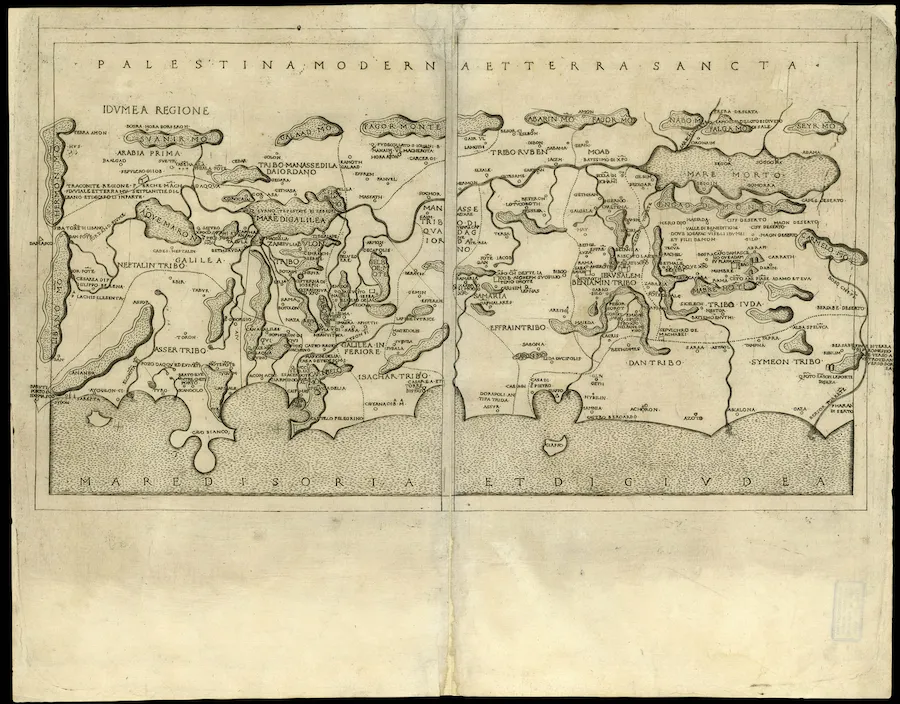

The reverence for Palestine in the Muslim world was not just spiritual but also underscored by its strategic importance and agricultural fertility. The cultural landscape of Palestine during this era was profoundly shaped by various Muslim dynasties, such as the Mamelukes and Seljuks. The area became well known to Muslims and Non-Muslims alike as Palestine. For example the following European map from the 1400s clearly indicates the name Palestine as a land was known and well-established:

Map of Palestine published in Florence 1482 and included in the Francesco Berlinghieri expanded edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia (Geography)

Map of Palestine published in Florence 1482 and included in the Francesco Berlinghieri expanded edition of Ptolemy’s Geographia (Geography)

Ottoman Rule

Section titled “Ottoman Rule”With the advent of Ottoman rule in 151, a new chapter for the history of Palestine began. Spanning four centuries, the Ottoman period was characterised by a predominantly Muslim and rural populace, interspersed with small urban Arabic-speaking elites. According to Israeli scholar Yonatan Mendel, the Jewish community comprised a minor fraction of the population, less than 5%, while Christians accounted for approximately 10-15% of the population:

The Jewish diaspora viewed Palestine as the Holy Land of the Bible. However, numerous Israeli scholars including David Grossman (the demographer), Amnon Cohen, and Yehoushua Ben-Arieh demonstrate that prior to the arrival of Zionist colonialists, Palestine was a thriving Arab society, predominantly Muslim and rural, but with dynamic urban centers.

Israeli scholar, Ilan Pappe further argues that the Ottoman-era Palestine mirrored its Arab neighbors, embodying the broader Eastern Mediterranean societal characteristics. Leaders like Daher al-Umar (1690-1775) played a pivotal role in fostering development of the area, enhancing trade links with Europe and neighbouring regions. Far from being a desert wasteland, Palestine was thriving and flourishing part of the Middle East with millions of inhabitants.

British Rule

Section titled “British Rule”Following the fall of the Ottoman empire and subsequent colonisation of the Middle East by European powers, Britain and France divided the region between each other in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. This became a crucial turning point in shaping Palestinian self-perception and aspirations for statehood. Britain was entrusted with the administration of Palestine, with the mandate also embedding the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised support for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. This created a foundation for conflict, as the local population opposed the idea of a Jewish state in their homeland.

From 1918, a more emboldened Palestinian identity had emerged. The British redrawing of borders in 1923 crystallized this identity, a clear geographical and national arena that would become the epicentre of the ensuing Zionist movement and the dispute over land ownership between in the native inhabitants and the colonists.

Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

Yonatan Mendel, The Creation of Israeli Arabic: Political and Security Considerations in the Making of Arabic Language Studies in Israel, London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014, p. 188. ↩